The Wisconsin Education Association Council (WEAC), the state’s largest educators union, has petitioned the Wisconsin Supreme Court to review the constitutionality of Act 10, a law limiting the collective bargaining rights of most public employees in the state. Filed on January 17 alongside several smaller unions, the petition challenges what the unions argue is an unfair division among public employees.

Act 10, also known as the Wisconsin Budget Repair Bill, was signed into law in 2011 by then-governor Scott Walker. Among other provisions, it restricts most public employees from negotiating working conditions beyond base wages, which are capped by inflation. However, those deemed “public safety employees,” like police officers and firefighters, can still negotiate over wages, hours and conditions of employment.

Act 10 has a long history of legal battles, most recently reignited last December when Dane County Judge Jacob Frost struck down key parts of the law. Frost found that the law’s distinction between public employees violates Wisconsin’s equal protection clause, calling its definition of “public safety employee” overly narrow.

WEAC and other unions have long argued that the law creates an unequal system, explains WEAC Public Affairs Manager Christina Brey.

“Carving out a certain group to have rights and others to not have rights goes starkly in opposition to what our constitution calls for: equal protection under the law,” Brey said. “That was the basis of our lawsuit [in December], which we were victorious in with the ruling that Act 10 is unconstitutional.”

More broadly, the WEAC believes that Act 10’s limitations on collective bargaining unfairly remove the voices of educators from conversations regarding educational policy.

“Here at the WEAC, we believe that public schools are better, stronger, and more able to meet student and family needs when educators have a voice in the workplace,” Brey said. “We oppose the bans on collective bargaining and we’ve been working really hard [since] 2011 to overturn this law just on the basis of its unfairness.”

Brey says that since its passage, the consequences of Act 10 have been far-reaching. For teachers, she argues that the loss of collective bargaining rights has contributed to decreasing compensation and high turnover, with many forced to leave the profession due to an absence of support that once made the job sustainable.

“Educators who once made a career out of teaching students in all corners of Wisconsin have seen their wages [and benefits] decline precipitously,” Brey said. “Without a voice, and without the respect of their administrators or schools to have a seat at the table, Wisconsin is in a severe educator staffing shortage, and every year it’s getting worse and worse.”

According to the latest report from the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction (DPI), inflation-adjusted median total compensation for teachers in the state has steadily declined over the 12 years studied (2010–2022). Median total compensation, here representing the midpoint of combined individual salary-and-benefit packages, peaked in 2011 at $102,576 before dropping to $93,211 in 2012. Ever since, it has fallen by a total of 19%, with brief and unsustained increases in 2016–2017 and 2020.

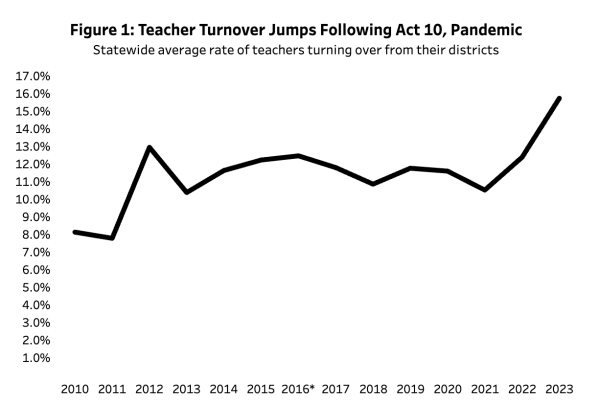

Additionally, turnover, which refers to teachers moving positions while staying within Wisconsin’s public education system, rose sharply following the passage of Act 10. According to DPI data analyzed by the Wisconsin Policy Forum, turnover rates went from 7.8% in 2011 to 13% in 2012 and have remained above 10% since. The analysis also notes, however, the possibility that pre-Act 10 turnover rates were unusually low because of lingering Great Recession effects motivating some to delay job changes.

Despite these criticisms, proponents of Act 10 argue that the law has brought important benefits, particularly in shifting power over budgets from unions back to local governments. Patrick McIlheran, Director of Policy at the Badger Institute, a non-partisan organization supporting free markets and limited government, believes that Act 10’s provisions protect taxpayers from spiraling costs brought on by government spending resulting from union advocacy.

According to McIlheran, exceptions made for public sector employees pre-Act 10 both played a significant role in driving up costs for taxpayers and created an unfair distinction between public and private-sector employees; for instance, the fact that, in general, public-sector employees paid a notably lower percentage of their healthcare coverage than private-sector employees. Now, under Act 10, employers are required to pay no more than 88% of the average premium costs of employee healthcare plans.

“The reason that employers want employees to share some of the cost of health insurance is because it gives employees a stake in whether that insurance is a good value,” McIlheran said. “If it’s a good value, then the employees make out well; they’re paying less for a good product. There was no such incentive in the Wisconsin public sector before Act 10. It made public-sector employees a different class of people than everyone else in the state, and it wasn’t very fair.”

McIlheran notes that, prior to Act 10, two-thirds of Wisconsin’s school districts purchased health insurance for their employees from WEA Trust, a company founded by WEAC. According to a pre-Act 10 study conducted by the Badger Institute, WEA was more profitable than other health insurers and generally charged more for services. McIlheran says this factor contributed to high costs for taxpayers.

“WEAC’s insurance wasn’t especially good, but it was very expensive,” McIlheran said. “Then, of course, WEA Trust was a non-profit insurer, but that didn’t mean it didn’t rake in a lot of money, and that funneled money to the union for political activity. It was a fundraising technique, essentially, and taxpayers were on the hook for it. It’s one of the reasons that health coverage was so overpriced in the public sector. Act 10 said you couldn’t do that any more.”

Under state and federal law, WEA Trust is a separate legal entity from the union, with no financial transactions permitted between the two. While WEAC was involved in the creation of WEA Trust, there is no decisive evidence determining whether or not WEAC held direct financial control over the insurer.

For McIlheran, however, such concerns highlight why Act 10 was necessary. He argues that unchecked union demands had contributed to skyrocketing costs in the public sector.

“[Unions] behaved and demanded unreasonable things; this led to spiraling costs,” McIlheran said. “This led to taxpayers revolting over the rapidly rising cost of government, especially on property taxes. It was leading toward fiscal ruin. That’s what Act 10 saved us from—it moderated the increase in the cost of government.”

Many local unions align with WEAC in opposing the law, including Shorewood’s teachers union, the Shorewood Education Association (SEA), which represents many of the district’s teachers and support staff. According to Amy Miller, SEA president and Lake Bluff teacher, while district administrators have continued positive relations with the SEA, the union is limited in its ability to negotiate meaningful working conditions beyond inflation-adjusted wages.

“With collective bargaining, we would be able to talk about many different things that would positively impact teachers’ working conditions, which are students’ learning conditions,” Miller said. “There is genuine desire to listen and to learn from each other, but, legally, we can’t go beyond ‘meeting and conferring.’”

Still, Shorewood has continued practices like its steps-and-lanes-based single salary schedule, even as school districts across the state have not, according to a 2016 study done by the Wisconsin Center for Education Research. Though exact figures are uncertain, many districts opted to redesign their pay schemes following the passage of Act 10, diverting from the decades-long standard of the single salary schedule.

Jay Lowery, SEA building representative and SHS teacher, says Shorewood’s maintenance of its pay schedule has incentivized teachers to remain and retire within the district.

“Having high-quality, experienced teachers that stay in the profession and in the district for a long time benefits students, their families, and the community,” Lowery said. “I’m able to work in a district that allows me to have some autonomy, to have some say over my working conditions, to have a salary that supports my family…If you are working in a place where you don’t have voice over your working conditions…not having as much take-home pay is a disincentive.”

McIlheran, on the other hand, argues that the discretion Act 10 gave school districts over teacher pay schemes ultimately benefits students.

“Schools were set free to offer more pay in exchange for higher-quality teaching, so they were able to attract better teachers to harder jobs,” McIlheran said. “Unions will tell you, ‘it’s unfair, we should be in charge of things again.’ They will also say, ‘this has hurt education.’ No, in fact, it hasn’t. The best evidence we have is that Act 10 allowed for more innovation in schools and it has improved the education available to Wisconsin kids.”

In examining data from students in grades three to eight, a 2024 Yale study assessing the impacts of Act 10 found that there was an increase in standardized test scores after the law’s implementation, especially for students who qualify for free or reduced lunches or are otherwise disadvantaged. The study explains that this is a consequence of changes in the market for teachers after Act 10.

Lowery also argues that the money Act 10 may save school districts and local governments comes at the expense of teacher pay and broader educational outcomes. However, Lowery believes that individual school districts are often not to blame for the bill’s adverse impacts on educators.

“The state of Wisconsin is sitting on a four-and-a-half-billion-dollar surplus,” Lowery said. “If those funds were released in an equitable way to districts in a post-Act 10 environment…that could and should be money that’s coming from the state. Districts are hurting; Shorewood’s one of them. A lot of that is not by fault of the district or the board or the administration—a lot of this comes back to the state.”

While union membership is voluntary under Act 10, Miller says that more than 80% of Shorewood staff are SEA members. Should Act 10 be ruled unconstitutional by the state Supreme Court, Miller hopes to resume broader union advocacy at the district level.

“We would want to sit down at the table with our employers and negotiate a contract,” Miller said. “It’s going to be a slow process. We have lots of people, lots of administrators, and lots of teachers who lead their teachers unions, who have never had experience negotiating the contract. So, it will be an intentional process.”

The Shorewood School District was not available for comment regarding its perspective on the issue and potential implications for Shorewood following the anticipated spring Supreme Court decision.

Conversely, McIlheran argues that upon a decision invalidating Act 10, the Wisconsin legislature’s first priority should be to pass legislation similar in scope to Act 10 in order to maintain the protections for taxpayers he understands the law to provide. Additionally, McIlheran believes that striking down Act 10 would limit the freedom of many public sector employees to choose union membership.

“The membership in the WEAC fell immediately; it’s now about half of what it was pre-Act 10 because, as it turns out, about half of its members didn’t want to be in the union and didn’t want to pay the expensive dues,” McIlheran said. “They gained the freedom because of Act 10 not to join a voluntary organization. If Act 10 gets knocked down, that freedom is over. The half of teachers who don’t want to be in the union aren’t going to have any choice; the money’s going to be taken from them anyway. The legislature needs to act if Act 10 goes away to restore that liberty because our public sector employees deserve it. They deserve that freedom to make that decision on their own.”

The outcome of the legal battle over Act 10 hinges largely on the composition of the state Supreme Court. In light of Justice Ann Walsh Bradley’s retirement, the winner of an April 1 election between liberal Susan Crawford and conservative Brad Schimel will fill an open seat on the court, which could flip the current 4-3 liberal majority. However, even in the case that Susan Crawford wins the election, the ideological balance of the court as it presides over Act 10’s legal challenge is still uncertain.

Prior to her election to the state Supreme Court, Justice Janet Protasiewicz marched in opposition to the law and expressed her belief that it was unconstitutional; as a result, Protasiewicz may recuse herself from the case, although she has not yet released a formal statement of her decision. Should Protasiewicz recuse herself, even with Crawford on the court, it is possible that a deadlocked 3-3 split will ensure Act 10’s survival.

Looking ahead, McIlheran warns against what he predicts may be a hasty decision in the spring.

“I would hope that the Supreme Court sees how much good has come from Act 10 and realizes that it’s a bad idea to overturn some law to favor a special interest, [the special interest being] unions,” McIlheran said. “But, I don’t know whether they will. The majority on the state Supreme Court seems to already have made up its mind that unions deserve more power and the rest of Wisconsinites deserve less.”

Lowery believes the positive reception surrounding the December ruling is premature and anticipates an uphill battle as the case moves to the Supreme Court. His hope, however, is to see collective bargaining rights restored.

“Just to put it simply, I’d love to see how it was in 2010, prior to the nightmare of Act 10, [where] teaching [is still] considered a profession where we can have an impact and still have some say over what our day looks like, and make a decent living doing so,” Lowery said.

Sources:

- To substantiate Pat McIlheran’s claims about WEA Insurance:

- https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED457591

- https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED457591.pdf

- https://www.barbarabiasi.com/uploads/1/0/1/2/101280322/political_feasibility.pdf

- https://wcer.wisc.edu/docs/working-papers/Working_Paper_No_2016_5.pdf

- https://dpi.wi.gov/sites/default/files/imce/education-workforce/pdf/2022-wi-epp-workforce-annual-report.pdf

- https://dpi.wi.gov/sfs/statistical/basic-facts/district-tax-levy-rates

- https://wispolicyforum.org/research/revolving-classroom-doors-recent-trends-in-wisconsins-teacher-turnover/