Warning: The following review contains light and fairly-general spoilers for The Boy and the Heron. Proceed with caution!

For the six decades that he has been making movies, Hayao Miyazaki has been quietly, yet persistently disrupting the conventional role of the child protagonist in the Western audience’s imagination. In their attempts to understand and connect with children’s experiences, studios like Disney often end up inadvertently infusing their own adult concerns and values into narratives around children, those of which are usually hyper-superpowered and prodigious, great destinies stretching out ahead of them. But Miyazaki’s characters are not so exceptional – they are, in fact, deeply, refreshingly ordinary; complex, flawed, and fully realized beings in their own right. In some ways, they are innocent and pure, but they are also fiercely stubborn, selfish, and capable of great cruelty. They feel the weight of the world on their shoulders, and they struggle against the expectations placed upon them by their elders. They are like us, yet also often elude us.

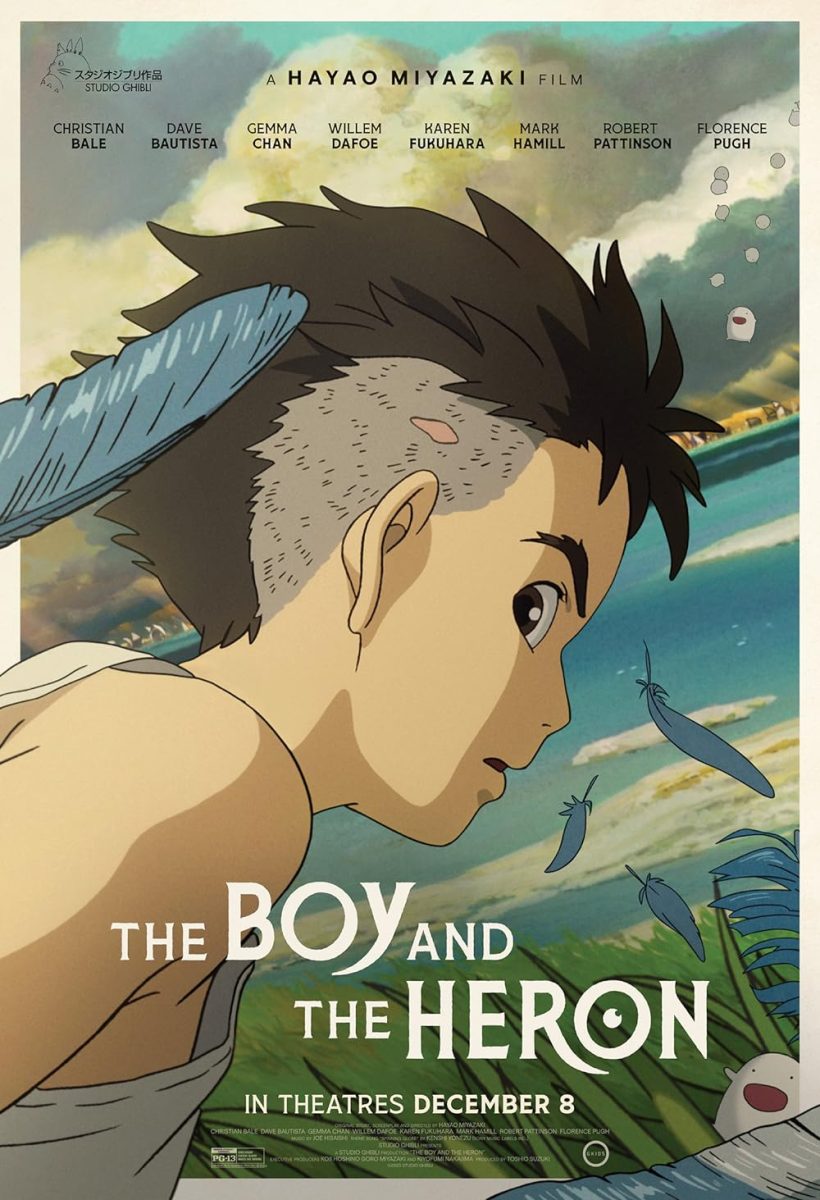

Miyazaki’s latest, The Boy and the Heron, no less embodies this idea. In the film, Miyazaki grapples with his own artistic legacy, baring his soul with a stark honesty that feels both familiar and profoundly new. Familiar, because it arrives in packaging similar to many other Studio Ghibli films, bearing many recognizable markings: those of haunting intensity (Princess Mononoke), fantasticality (Spirited Away), and a great amount of tenderness (My Neighbor Totoro). In almost all other aspects, however, it is not like any of Miyazaki’s previous works, and is perhaps the most personal of them all. Put aside your expectations for the Miyazaki of old, or discover him anew, by asking the all-important question: how do you live?

That very same question is also the original Japanese title of the film, adopted from a 1937 novel by Genzaburo Yoshino. The book and film differ in almost every other way, and so the title serves more as yet another lens to consider the work through. Set in the dual environments of both actual and imagined World War II-Japan, Miyazaki channels both various pieces of literature as well as his own experiences through the character of Mahito Maki, whose life has been upended by the tragic loss of his mother in a hospital fire. Mahito’s father remarries Natsuko, and they evacuate to her rural estate. Mahito, initially distant from Natsuko, encounters a talking gray heron that leads him to a sealed tower in the woods, the last known location of Natsuko’s granduncle, an architect. We follow Mahito as he grapples with grief and the emotional aftermath of tragedy through his quest for self-discovery.

But grief must be understood on its own terms, followed through the twists and turns of its logic, before it can be apprehended. It’s a process, like any other process, and must be allowed to run its course. It takes in many ways, and it is often only once we stand barren, bereft of all things, do we find them returned in forms anew. Of course, in some way or another, we eventually follow it, half-reluctantly, as if drawn by some irresistible force, and find ourselves standing before open grave, staring into the empty space where once there had been life. Mahito realizes this when his journey eventually leads him into a fantastical oceanic world where he is forced to face his loss, his own emotions after the fact, and the very fate of the world itself.

When Mahito must decide what the future will look like for him, Miyazaki makes a point that it is not the burden of the next generation to unconditionally inherit and fix the mistakes of their predecessors. Similarly, Mahito refuses to shoulder this massive burden of the world. The boy and the heron, the forest and the tower, the fields and the stars hanging above them: these are the things that really matter, that give us purpose and meaning in a world that would all too easily have us fade into the background.

The film also makes significant sociopolitical commentary. The Warawara, a species of unborn human souls dwelling in the Sea World, seek to mature and ascend into the sky to be born as humans. Before many can, though, the pelican species interferes, both a literal and metaphorical barrier to the continuation and renewal of life. The pelicans, who eat Warawara out of gnawing necessity, unwittingly embody the fears and resistance of older generations to the inevitability of change.

Gender roles also play a prominent part in Mahito’s life. When Mahito faces significant struggle following the death of his mother and emotional detachment of his father, Mahito’s father retreats further into the purely-militaristic and traditionally masculine. When Mahito goes missing, he engages in intense preparation, packing supplies and weapons, and sets out determinedly, as if he is ready to go to war to find him. The female characters play more maternal, nurturing, and mentoring roles, acting as guide figures for Mahito along his journey and contributing to the upkeep of life and the intricate ecosystem.

The protagonists of Miyazaki’s films are, simply put, children. They are expected to learn, to grow, and to change; yet, they are not expected to save the world. In fact, it is this very lack of expectation that allows them to save themselves. Here, we see the characters simply going about their business, doing what needs to be done, without the heavy-handed moralizing or sentimentality that so often accompanies stories of children finding their place in the world. Perhaps the most striking difference lies in the treatment of their agency. It is not a burden forced upon them, but a natural extension of their being. This is not to romanticize childhood – Miyazaki’s young protagonists often grapple with fear, doubt, and selfishness. They fledge arrows and notch them the next day, ready to do battle. They steal cigarettes and bribe blacksmiths to teach them knife sharpening. They must learn from their mistakes and grow. But they are never stripped of their essential childhood, their way of seeing honestly, their curiosity and inner drive. Even as they face great perils, their clarity of spirit remains intact, and they never truly lose sight of what matters most.

Miyazaki’s vision here is expansive, exploring themes of war, loss, identity, and the interconnectedness of all things – organisms, generations, institutions – packing them all into a two-hour, four-minute runtime. And while not his strongest work, The Boy and The Heron is unassailably a beautiful and touching film. It won’t leave you with easy answers or a sense of closure; rather, its success depends on the audience’s willingness to surrender belief and accept its flaws as part of its unique charm. In the words of Miyazaki himself, “Perhaps you didn’t understand it. I myself don’t understand it.”

The question of how do you live? gives way to many others. Are we better off perfecting a world of our own, free from the pain and chaos of our uncontrollable lives? Or should we pursue peace and acceptance in what small corners we can find, even within a world upside down? We live in a world where a single choice can alter the course of a life, a world where the line between right and wrong is razor-edge-thin. And yet, we persist. We build our castles, knowing that ocean waves will come to lap at the walls. We plant our gardens, even as weeds and thorns threaten to choke them out. We love, even when we know the pain it brings. And so, we go on. We are human, and this is our story. Welcome to it.