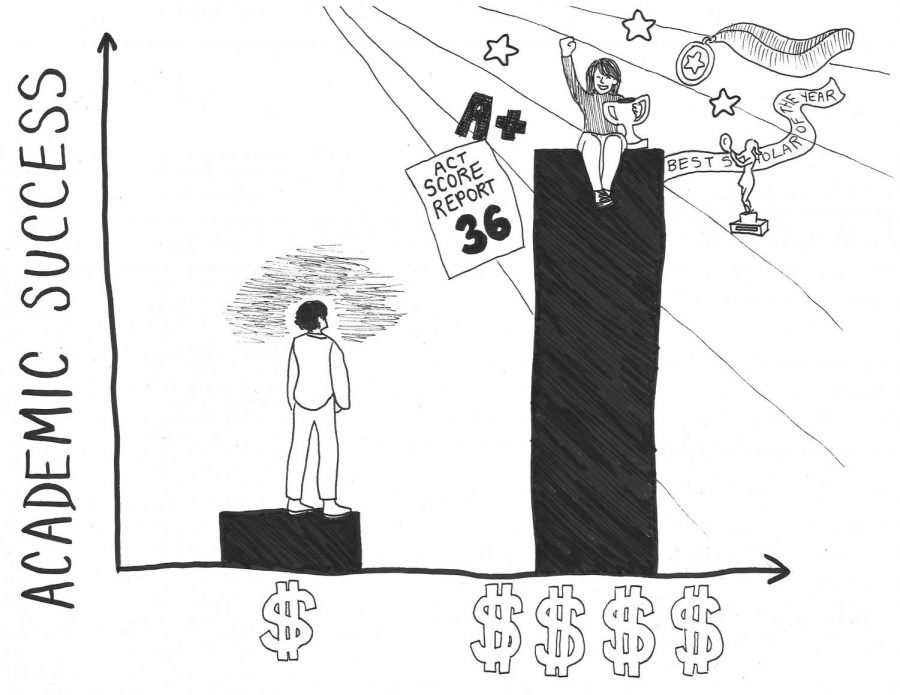

How wealth impacts academic success

In March of this year, Lori Louglin, Felicity Huffman and about 50 other families were implicated in an FBI investigation nicknamed “Operation Varsity Blues,” which is currently investigating privileged families who used their money and power to get their children into elite level colleges, including universities such as Yale, Georgetown, USC and UCLA.

While this situation seems as though it is a much more direct abuse of power and privilege than anything that occurs in Shorewood or most other wealthy public school districts in the United States, it is still a consistent pattern that students of the wealthiest families are given an advantage in these school districts because of the greater resources their families are able to provide to them.

In 2016, The New York Times released an article called, “Money, Race and Success: How Your School District Compares.” The article compares the average scores of a sixth grader on a standardized tests with the average income in the district that sixth grader is from. The first finding of the article is something that will surprise very few, the schools with the highest average income were more likely to have students grade levels ahead of average.

For example, a student at Shorewood, with an average income of $96,000, was on average 1.9 grades above average, but a student at a school in Milwaukee, with an average income of $32,000, was 2 grades below average. Another finding of the article and an analysis lead by Stanford researchers, was that even in rich municipalities, Berkeley, California and Kenilworth, Illinois, for example, a large test score gap exists between poorer and richer students, and students of white families versus students of black and hispanic families. So why does this happen? Why do two students who are placed in the same district with the same advanced curriculums consistently score different on various standardized tests?

There are many advantages that someone who comes from a rich family might have that could give them a leg up in school, the first being having a stay-at-home parent. Families that can afford for one parent to stay at home to help their child with various extracurriculars and homework can aid their child’s academic development. When I was in elementary school, I noticed advancing in math was easier for kids that had a parent with time to be able to spend their summer working on math with their child.

Another advantage to having a stay-at-home parent, or even an over-involved, competitive or ambitious parent, is the advocacy that they can do. Parents, and even students, network and discuss the most challenging classes, teachers and tracks a student can be placed on. Getting students in the most difficult classes with the most challenging teachers helps those students to be successful in the future.

Parent’s careers and education level also creates a test score gap between students. If parents have PhD’s, for example, or happen to be really knowledgeable about what they are learning in school, they can easily get help their children with homework. This makes the learning that happens at some homes greater than the learning that happens at other homes. The point of this is not to say that it is bad for parents to push their kids and help their kids to do their best in school. A lot of parents do that. Rather, we need to be more aware of how money and privilege helps their kids in school. How can this change, and how can it matter less what you are given outside of school by your parents, and matter more your work ethic, your natural capability and your desire for more knowledge?

This is a question that I think people in Shorewood have to ask themselves. How can the classes we take set every student up for the same amount of success? There may not be hundreds of thousands of dollars in bribes flying around, but our education system still suffers from the same disease.